In honor of Chipeta’s recognition during National Women’s History Month, here is a post about her 1880 testimony before a Congressional Committee investigating the Meeker Massacre in Colorado. This post originally appeared on this blog March 24, 2009.

Chipeta by Mathew Brady, Washington, D.C., 1880

On March 19, 1880 Chipeta entered the Capitol building and took the witness stand facing a group of Congressmen seated behind a long table. Not yet 40 years old, she had lived her entire life in the Rocky Mountains. She was the wife of Chief Ouray and his most trusted advisor and confidant. She travelled to Washington, D.C. with a group of Ute chiefs. Secretary of Interior Carl Schurz welcomed her as a member of the delegation rather than as a tag-along wife.

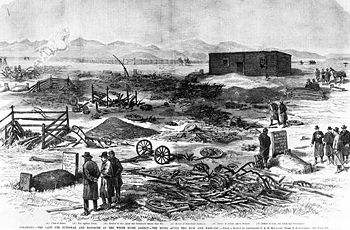

Her upcoming testimony was announced by The Washington Post, describing her as “a fat, good-humored looking squaw.” The reason for her appearance in the capitol city was an event that had captured national attention the previous year. A group of Northern Utes attacked a column of soldiers, murdered their Indian agent, Nathan Meeker, and all male employees of the agency. They spirited three white women and two children into the high mountains as hostages. Newspapers across the nation followed the unfolding events for the next 30 days until the hostages were safely released.

In the Congressional hearing, Chipeta responded (through an interpreter) to ten questions about where she was when the massacre took place and what caused the events. Most of her answers amounted to “I don’t know” because she had not been present at the massacre. She told the committee some of the Indians said Agent Meeker “was a bad man, that he talked bad…Some of them claimed that he was always writing to Washington and giving his side of the case, and all the troubles at the agency…I do not know whether that is what they killed him for, or what they did it for.”

Source: Testimony in Relation to Ute Outbreak, 46th Congress, 2nd Session, House Miscellaneous Documents no. 38, 1880, 91.

The 5th Cavalry under

The 5th Cavalry under